The Hejaz Railway: From Ottoman Dream to 2026 High-Speed Revival

Table of Contents

The Hejaz Railway was never just about trains. It was the internet of the early 20th centurythe masterstroke of Ottoman modernization that connected three continents. Built under the visionary gaze of Sultan Abdülhamid II, it didn’t just lay tracks across the desert; it compressed time itself, shrinking the grueling 40-day camel trek between Damascus and Medina into a manageable 5-day journey.

Its primary goal was strategic and spiritual: to link Istanbulthe seat of the Caliphatedirectly to the holy cities of Medina and Mecca. It was designed to give pilgrims, soldiers, and trade goods a safe passage through the unforgiving desert, effectively stitching the Islamic world back together.

The History: An Impossible Engineering Feat

The dream of a railway into the Hejaz began as early as 1864, but it was dismissed as technically impossible and financially ruinous. By the late 19th century, the Ottoman Empire established by Osman I and expanded into a global superpowerwas facing immense pressure from European powers. In this climate of uncertainty, the railway became a symbol of defiance and survival.

Sultan Abdülhamid II resurrected the idea to tighten Istanbul’s grip on its distant Middle Eastern provinces. Much like the reforms of Sultan Mahmud II, this was a modernization project, but with a distinctly Pan Islamic flavor.

In 1900, the order was given. The plan was audacious: connect the new line to the existing Anatolian and Baghdad Railways, creating an unbroken steel artery from the Bosphorus to Medina. While a further extension to Mecca and the Red Sea port of Jeddah was planned, political chaos prevented it from ever happening. Alongside the tracks ran a telegraph line, revolutionizing communication across the empire faster than the trains themselves.

Why Build It? More Than Just Faith

The Hejaz Railway wasn’t just a religious charity project; it was a geopolitical masterclass serving three distinct purposes.

1. Religious Duty

For centuries, the Hajj was dangerous. Pilgrims faced bandit raids, dehydration, and disease on the caravan routes. The railway offered a secure, affordable alternative, democratizing the pilgrimage for millions who previously couldn’t afford the risk or the cost.

2. Economic Boom

The line was designed to unlock the economic potential of the Levant and the Hejaz. It allowed agricultural goods to reach urban markets in days rather than weeks, integrating the remote desert economy into the global trade network.

3. Military Strategy

Militarily, it was a game changer. The Sultan could now deploy troops to Yemen or the Hejaz in days to quell rebellions. Politically, it was a statement of independence. By financing and building it without European banks, the Empire proved it could still execute monumental projects on its own terms.

Financing: The Crowdfunding Campaign of the Century

The cost was staggering: roughly 4 million Ottoman Lira, or about 18% of the entire state budget. Contemporary estimates place this at roughly 570 kilograms of gold.

Already drowning in debt to European creditors, Sultan Abdülhamid II refused to take foreign loans for this sacred project. Instead, he launched the world’s first global Muslim crowdfunding campaign. He personally donated 350,000 Lira, and leaders like the Khedive of Egypt sent raw materials.

The response was electric. Donations poured in from Muslims as far away as India and Morocco. To close the gap, the state got creative:

- Selling the hides of sacrificial animals during Eid al Adha.

- Issuing special “Railway Stamps” and taxes on official papers.

- A mandatory 10% deduction from civil servant salaries.

Amazingly, two thirds of the total cost was covered by these donationsa testament to the project’s powerful appeal to spiritual heritage and solidarity.

Construction: Blood, Sweat, and Sand

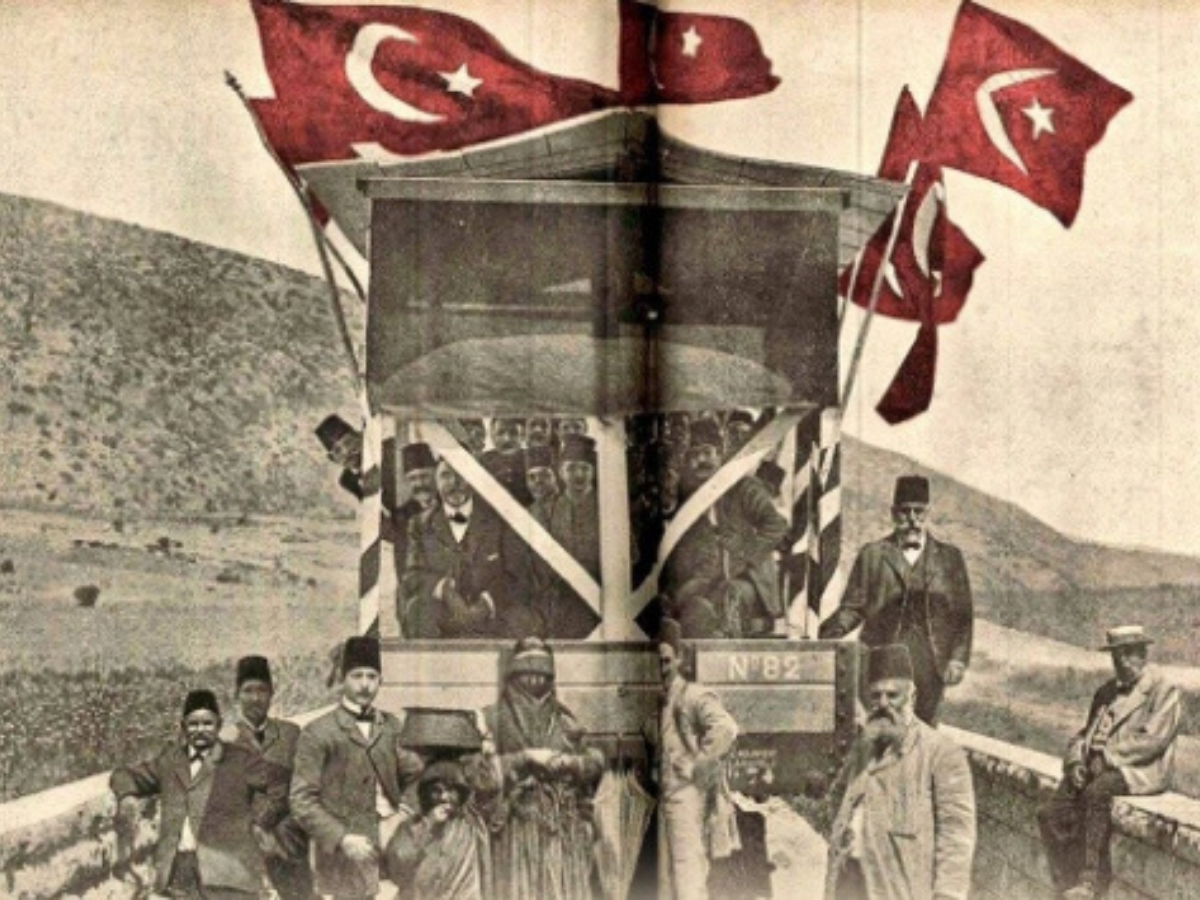

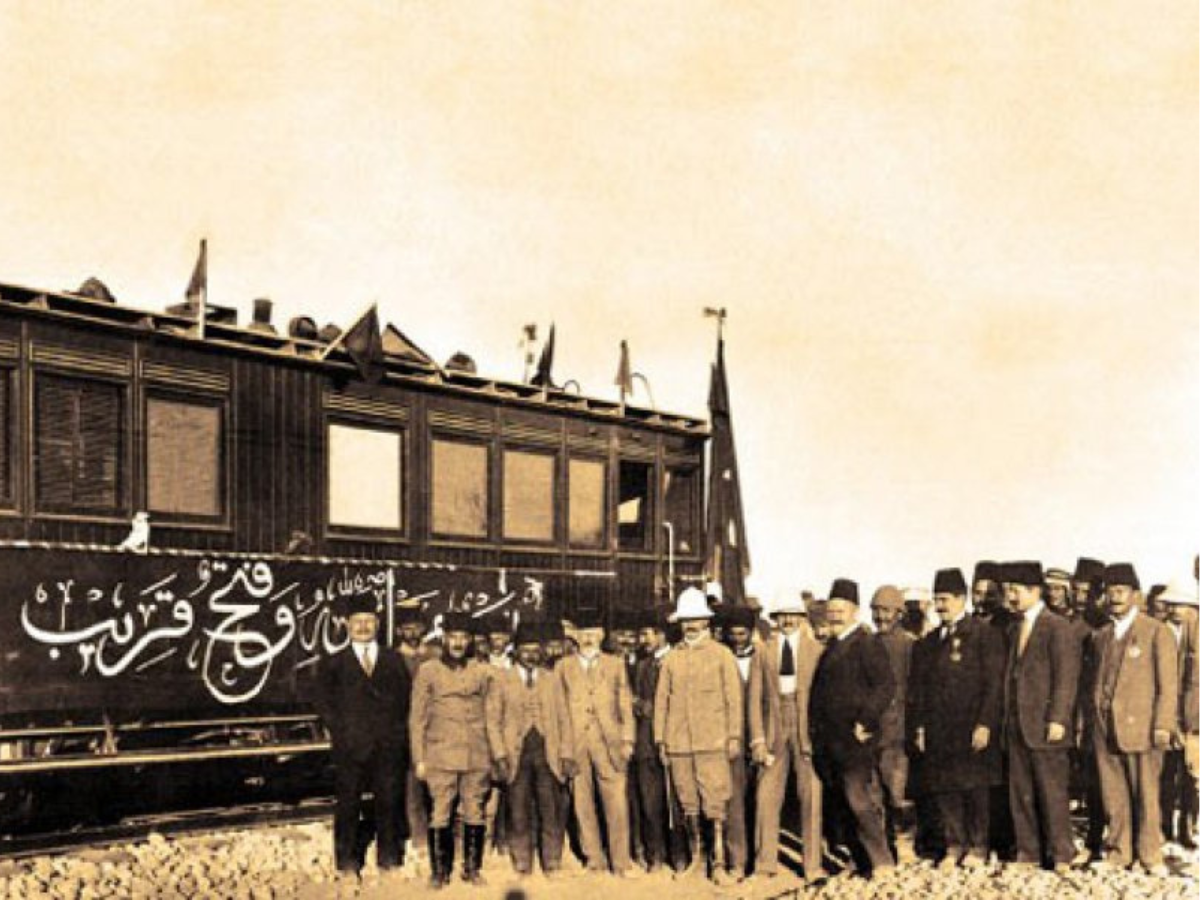

Construction kicked off on September 1, 1900. Led by the brilliant German engineer Heinrich August Meissner (Meissner Pasha), an army of up to 7,000 Ottoman conscripts worked alongside specialized technicians. The soldiers were motivated by a unique bonus: one year shaved off their mandatory military service.

They battled flash floods, sandstorms, and blistering heat. Yet, by 1908, the tracks reached Medina. In a gesture of profound respect, the final approach into the holy city was constructed entirely by Muslim engineers and laborers.

Key Stations Along the Route

Stations were built every 20 kilometers to ensure water access and security, effectively creating new towns in the void.

- Damascus: The grand starting point, designed in a stunning Andalusian style.

- Amman: A critical maintenance hub, 222 km south of Damascus.

- Tabuk: A massive complex with 13 buildings spread over 80,000 m², now a beautifully restored museum.

- Mada’in Saleh: Strategically vital, housing large repair workshops.

- Medina: The terminus, located just one kilometer from the Prophet’s Mosque. Today, it stands as the Hejaz Railway Museum.

The Fall: Lawrence and the Dynamite

The first train rolled into Medina on August 23, 1908. By September 1stthe Sultan’s jubileeMedina was illuminated by electric lights for the first time, powered by the railway’s generators. It was a triumph.

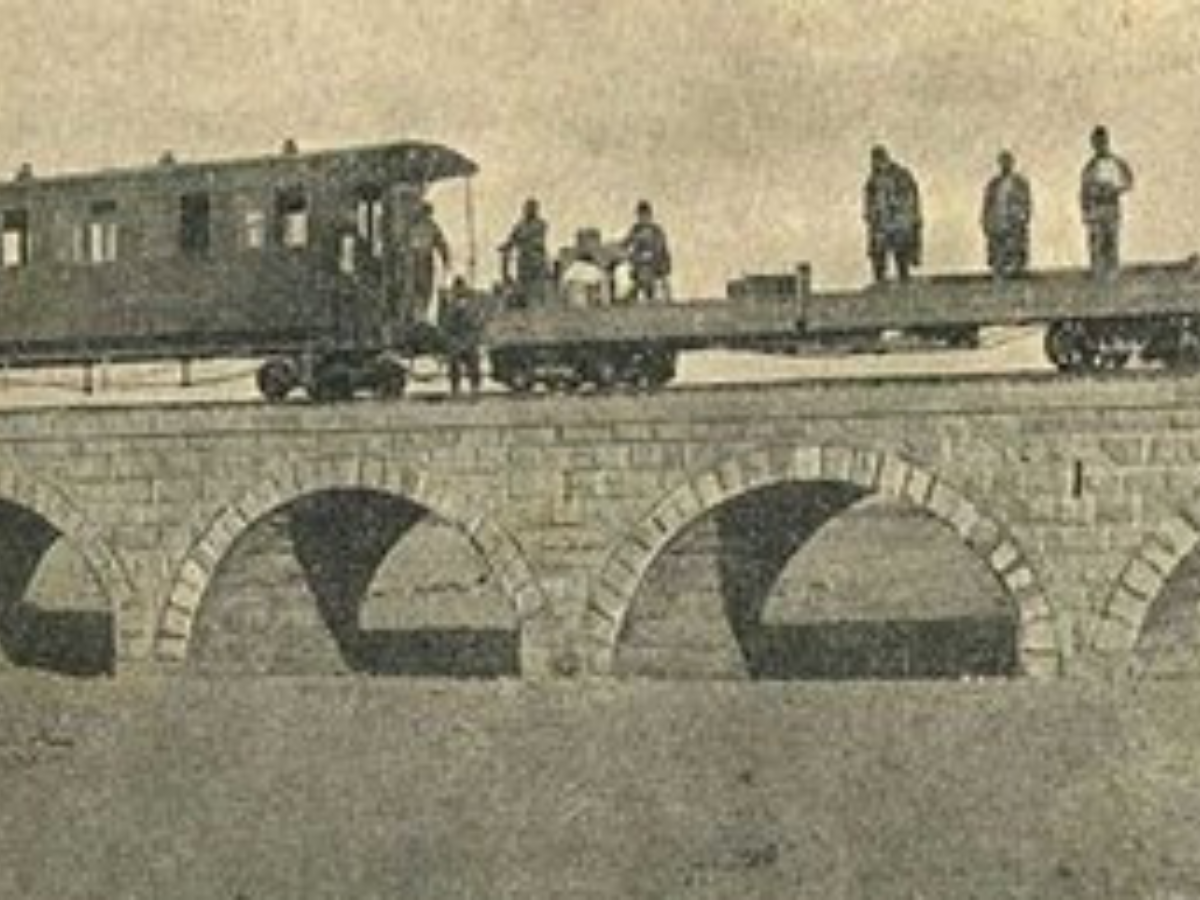

For a few short years, the railway flourished, carrying 300,000 pilgrims annually by 1914. But World War I brought a violent end to this golden age. Arab rebels, advised by the British officer T. E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”), launched a campaign of systematic sabotage. They blew up bridges and tracks to starve the Ottoman garrison in Medina. With the surrender of Fahreddin Pasha in 1919, the railway’s original purpose died in the desert sand.

The Hejaz Railway in 2025: A Modern Renaissance

Fast forward to December 2025. The ghost of the Hejaz Railway is coming back to life. Across Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Syria, the legacy is being rebuiltnot just as museums, but as modern steel.

Saudi Arabia: High-Speed History

In Medina and Tabuk, the historic stations have been preserved as world-class museums. The Hejaz Railway Museum in Medina has become a cultural beacon, drawing thousands of visitors daily.

But the real successor is the Haramain High Speed Railway. Rocketing between Mecca and Medina at 300 km/h, it is the spiritual successor to Abdülhamid’s steam trains. In the third quarter of 2025 alone, over 2 million passengers used this service. To meet this exploding demand, authorities have announced the fleet will expand by another 20 trains in 2026.

Syria: The Whistle Blows Again

In a symbolic breakthrough, August 2025 marked the resumption of train services between Aleppo and Damascus after a 13-year hiatus. The historic al Qadam station in Damascus is once again a functioning hub. This revival is part of a massive $5.5 billion infrastructure plan aimed at reconnecting Syria’s shattered network with its neighbors, Turkey and Jordan.

The Legacy Lives On

The Hejaz Railway remains one of history’s most fascinating chapters. What started in 1900 as a pious wish is still shaping the region today. Whether through the silent ruins in the Jordanian desert or the sleek high-speed trains gliding into Medina, the vision of connecting the faithful remains unbroken.