The Turkish Constitution: History, Principles & Key Reforms

Table of Contents

Think of the Turkish Constitution (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Anayasası) not merely as a dusty legal tome, but as the operating system of the Republic of Turkey. It defines everything from the structure of government to your fundamental rights as a resident or citizen. It is the framework that holds the entire political and social fabric of the nation together.

Currently based on the 1982 text, this document is the supreme law of the land. However, it hasn’t stayed static. It has been patched and updated numerous times to align with democratic standards, most notably with the massive overhaul in 2017. That referendum wasn’t just a tweak; it fundamentally shifted the country’s engine from a parliamentary system to a centralized Presidential system.

Overview: Understanding Turkey’s Supreme Law

The current constitution was born out of turmoil. Drafted following the military coup of September 12, 1980, it was adopted by a public referendum on November 7, 1982, replacing the more liberal constitution of 1961.

While the original 1982 text was heavily influenced by military security concerns, the Turkey of today operates on a very different version. Through successive reform packagesdriven largely by EU accession talks in the 2000sthe text has been liberalized. Today, it guarantees broad civil liberties, though as any observer of Turkish politics knows, the application of these laws is where the real friction often lies.

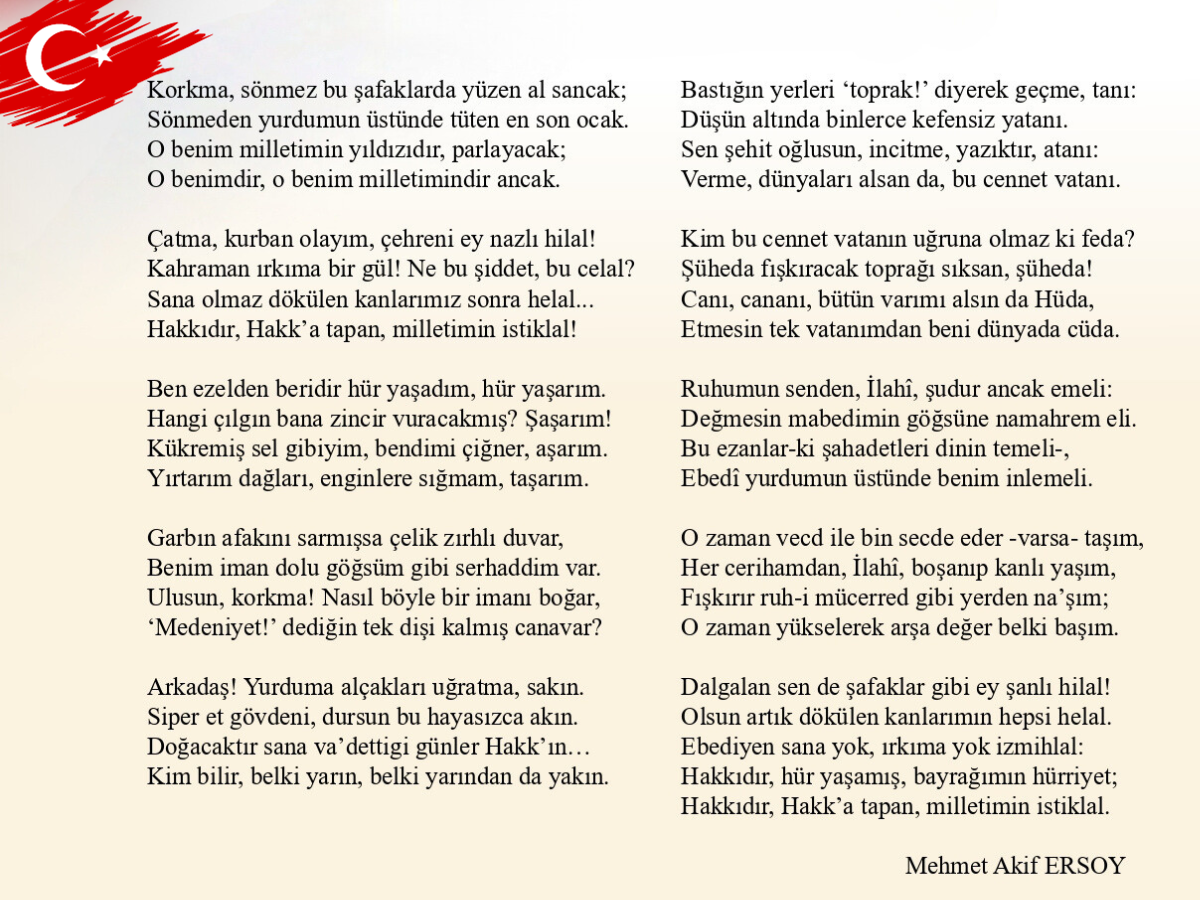

One critical feature you must understand is the concept of the “Irrevocable Articles.” The first three articles of the constitution are legally untouchable. Protected by Article 4, they define the state’s form, language, flag, anthem, and capital. They cannot be changed, nor can anyone even propose to change them.

A History of Transformation

Turkey’s constitutional history is a mirror of its struggle to transform from a crumbling empire into a modern nation state. Each version marks a specific era in the country’s evolution.

1921: The War Constitution

Adopted on January 20, 1921, the Teşkilât ı Esasiye Kanunu was the first constitution of the new Ankara government. It was written while the War of Independence was still raging. Short, pragmatic, and revolutionary, it consisted of only 23 articles.

Its most radical declaration? “Sovereignty belongs unconditionally to the nation.” This single sentence effectively transferred legitimacy from the Ottoman Sultan to the people and their representatives in the Grand National Assembly.

1924: Founding the Republic

After victory was secured and the Republic declared in 1923, a new, comprehensive constitution was ratified in 1924. This document facilitated the sweeping reforms of the Mustafa Kemal Atatürk era, dismantling the old order to build a secular state.

- 1928: The clause defining Islam as the state religion was removed.

- 1930/1934: Women were granted the right to votefirst locally, then nationally. Turkey was years ahead of many European nations in this regard.

- 1937: The principle of Laicism (Secularism) was formally enshrined in the constitution.

1961: Checks and Balances

Following the 1960 coup, the 1924 constitution was scrapped. The 1961 replacement is often cited by historians as the most liberal in Turkish history. It introduced strong checks and balances to prevent the concentration of power.

- It established the Constitutional Court to review legislation.

- It created a bicameral parliament (National Assembly and Senate).

- It granted autonomy to universities and public broadcasting.

1982 and the Shift to the Presidential System

The pendulum swung back after the 1980 coup. The 1982 constitution returned to a unicameral system and strengthened the executive branch, prioritizing state authority over individual liberties. However, the most significant shift in modern history occurred with the 2017 Referendum.

This reform fundamentally altered the DNA of Turkish governance, moving the country to an executive Presidential System:

- The office of the Prime Minister was abolished.

- The President became the sole head of the executive branch (Head of State and Government).

- Parliamentary seats were increased to 600.

- The President gained the ability to issue decrees and retain political party membership.

For investors, this centralization means the regulatory landscape can change rapidly. If you are looking into starting a company in Turkey, understanding that presidential decrees can swiftly alter commercial rules is vital for your risk assessment.

Inside the Constitution: Key Principles

The Unchangeable Core

The first four articles are the ideological bedrock of the Republic. Article 1 declares the state a Republic. Article 2 defines it as a “democratic, secular, and social state governed by the rule of law.” Article 3 cements national unity, the Turkish language, the flag, the national anthem (İstiklâl Marşı), and Ankara as the capital.

Understanding these administrative basics is crucial even for daily life tasks, like navigating the Turkish address format when dealing with official bureaucracy.

Rights and Duties

The second section details fundamental rights: personal liberty, privacy, freedom of expression, and social rights like education and labor. While the constitution guarantees the right to work, navigating the local job market as a foreigner has its own set of rules. For a practical look at how these rights translate to reality for expats, check out our guide on finding a job in Turkey.

The Constitutional Court: The Referee

The Constitutional Court (Anayasa Mahkemesi), located in Ankara, acts as the guardian of the constitution. Composed of 15 members, it serves two primary functions:

- Judicial Review: It checks laws and presidential decrees to ensure they comply with the constitution.

- Individual Application: Since 2012, citizens can appeal directly to this court if they believe the state has violated their fundamental rights and all other legal avenues have been exhausted.

It also functions as the Supreme Criminal Court (Yüce Divan) to try high ranking officials, including the President or Ministers, for crimes related to their duties.

FAQ: Amending the Constitution

Changing the constitution is a deliberate and difficult process designed to ensure consensus. A proposal requires the support of at least one third of the 600 MPs (200 signatures). From there, two hurdles exist:

- 360 to 399 Votes (3/5 Majority): The amendment is passed by parliament but must be submitted to a public referendum for final approval.

- 400+ Votes (2/3 Majority): The President can sign the amendment directly into law. However, the President retains the right to call for a referendum voluntarily, even with this supermajority.