The Ottoman Tughra: Decoding the Sultan’s Calligraphic Seal (2026 Guide)

Table of Contents

Imagine a signature so powerful that forging it was punishable by death. Before modern corporate branding dominated the world, the Ottoman Empire perfected the ultimate logo: the Tughra. It wasn’t just a scribe’s doodle; it was the visual embodiment of the Sultan’s authority, combining intricate art with absolute political power.

If you are walking through Istanbul in 2026, you are likely looking at these symbols without realizing what they mean. They are hidden in plain sighton restored palace gates, inside historic mosques, and even in the language we use when flipping a coin. We aren’t just looking at ink on paper here; we are looking at a 600-year old code that defined an empire.

The Origin: It’s Not Arabic, It’s Oghuz

Contrary to popular belief, the concept of the Tughra didn’t start in the Arab world. It is rooted in Turkish nomadic tradition. In the 11th century masterpiece Dīwān Luġāt at Turk, the scholar Kaşgarlı Mahmud defined the term tuğrağ specifically as the seal or signature of the Oghuz ruler.

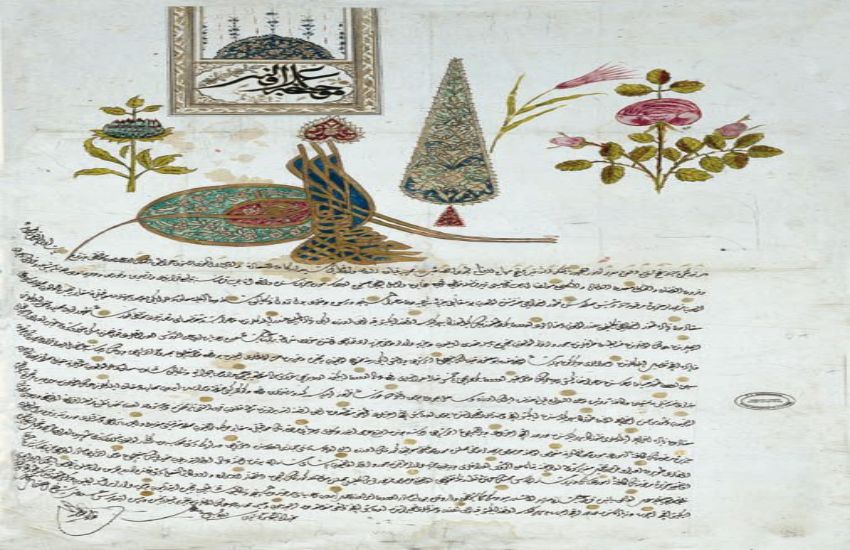

Originally, it may have represented a bow and arrow or a mythical bird, but by the time the Ottomans adopted it, it had evolved into a sophisticated monogram. The oldest surviving example we have in 2026 belongs to Orhan Gazi, found on a deed (vakfiye) dated March 1324. It started simple, but over centuries, it grew into the complex design we recognize today.

The Nişancı: The Man Behind the Ink

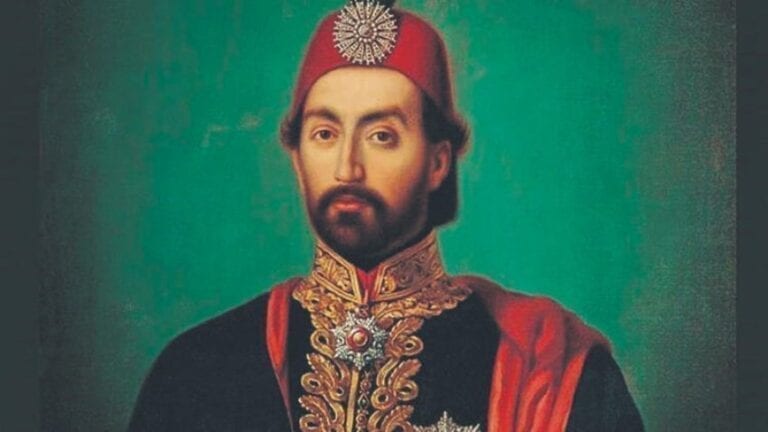

You couldn’t just hire a freelancer to draw a Tughra. This was a matter of state security. The task belonged exclusively to the Nişancı, a high ranking member of the Imperial Council (Divan ı Hümayun). Think of him as a combination of a Secretary of State and a Master Graphic Designer.

Until the position was abolished in 1836, the Nişancı was responsible for “pulling the Tughra” (tuğra çekmek) onto official decrees like firmans and land deeds. This wasn’t just about making it look pretty; it was about authentication. Just like getting married in Turkey today involves piles of paperwork to prove legitimacy, the Tughra was the final seal that made a document law.

- The Risk: Unauthorized painting of the Tughra was considered forgery of the Sultan’s authority and could lead to execution.

- The Skill: The Nişancı had to be a scholar, often a professor from a madrasa, ensuring the intricate Arabic script was flawless.

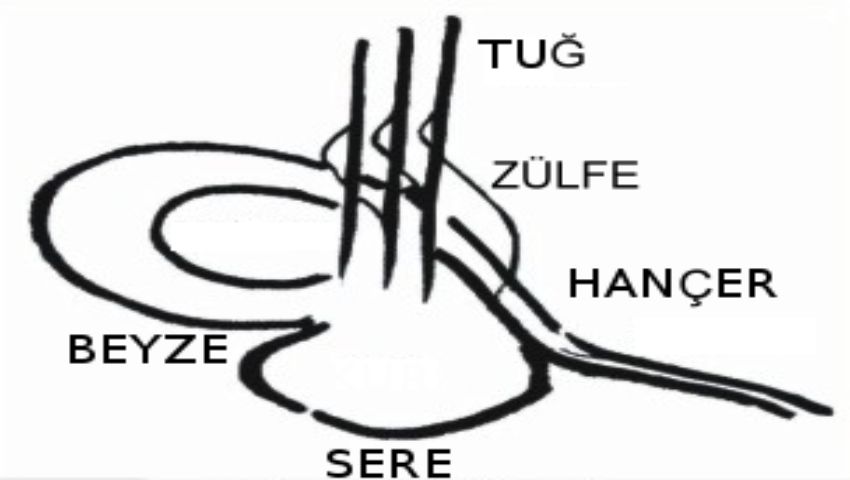

Anatomy of the Seal

A Tughra isn’t random scribbling. It follows a strict geometric anatomy that evolved from the simple signature of Orhan Gazi to the elaborate designs of Suleiman the Magnificent. Much like the distinct meter in Yunus Emre’s poetry, every curve in a Tughra has a specific name and purpose.

The standard form typically includes the Sultan’s name, his father’s name, and the phrase el muzaffer daima (“the always victorious”). By the 16th century, the width of these seals grew from a modest 7 cm to a massive 40 cm, matching the grandeur of the empire’s expansion.

Where to Find Them in 2026

While the Ottoman Empire is long gone, its logos have proven incredibly durable. Thanks to recent restoration efforts, you can see pristine examples right now if you know where to look.

1. Topkapi Palace (Bab ı Saadet)

If you visit the “Gate of Bliss” at Topkapi Palace in 2026, look up. The keystone features the Tughra of Sultan Mahmud II, penned by the legendary calligrapher Mustafa Rakım Efendi. Following an extensive restoration by the Presidency of National Palaces that concluded in 2024, the gold leaf and script are currently in their best condition in a century.

2. The German Fountain (Alman Çeşmesi)

Located in Sultanahmet Square, this monument is a unique hybrid of East and West. Inside the dome, you will see the Tughra of Sultan Abdulhamid II alternating with the “W” monogram of Kaiser Wilhelm II. As of January 2026, these mosaics are fully visible and remain a testament to the political alliance of 1900.

3. Pristina, Kosovo

The Tughra’s reach wasn’t limited to Istanbul. In Pristina, the Yaşar Mehmed Paşa Mosque (built 1834) proudly displays Sultan Mahmud II’s Tughra above its main portal. TİKA (Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency) completed a major restoration here in 2015, and the mosque remains open for worship today, featuring stunning Ottoman Baroque interiors.

The Ban and The Survivor: “Yazı Tura”

When the Republic was founded, the visual language of the state had to change. Law No. 1057, passed in 1927, mandated the removal of Tughras and Ottoman coats of arms from public buildings. Historically, this meant many were covered up or moved to museums. However, this does not mean they are illegal today.

In 2026, under Heritage Law No. 2863, the approach is preservation. We no longer chip them off; we restore them as cultural artifacts. The historic ban was about changing the regime’s identity, but modern Turkey embraces the history.

The most fascinating survival story, however, is linguistic. In Turkish, the “Heads” side of a coin is called Tura. This comes directly from the Ottoman tradition of stamping the Sultan’s Tughra on the obverse of coins. Even though modern coins feature Atatürk, the word stuck. So, every time you flip a coin to decide who pays for tea, you are referencing the Sultan’s seal.

Planning to send a letter or decipher an address in Istanbul? Check out our guide on Turkish Address Formats to ensure your own “documents” get to the right place.