Tugra : tout ce que vous devez savoir sur ce symbole ottoman

Table of Contents

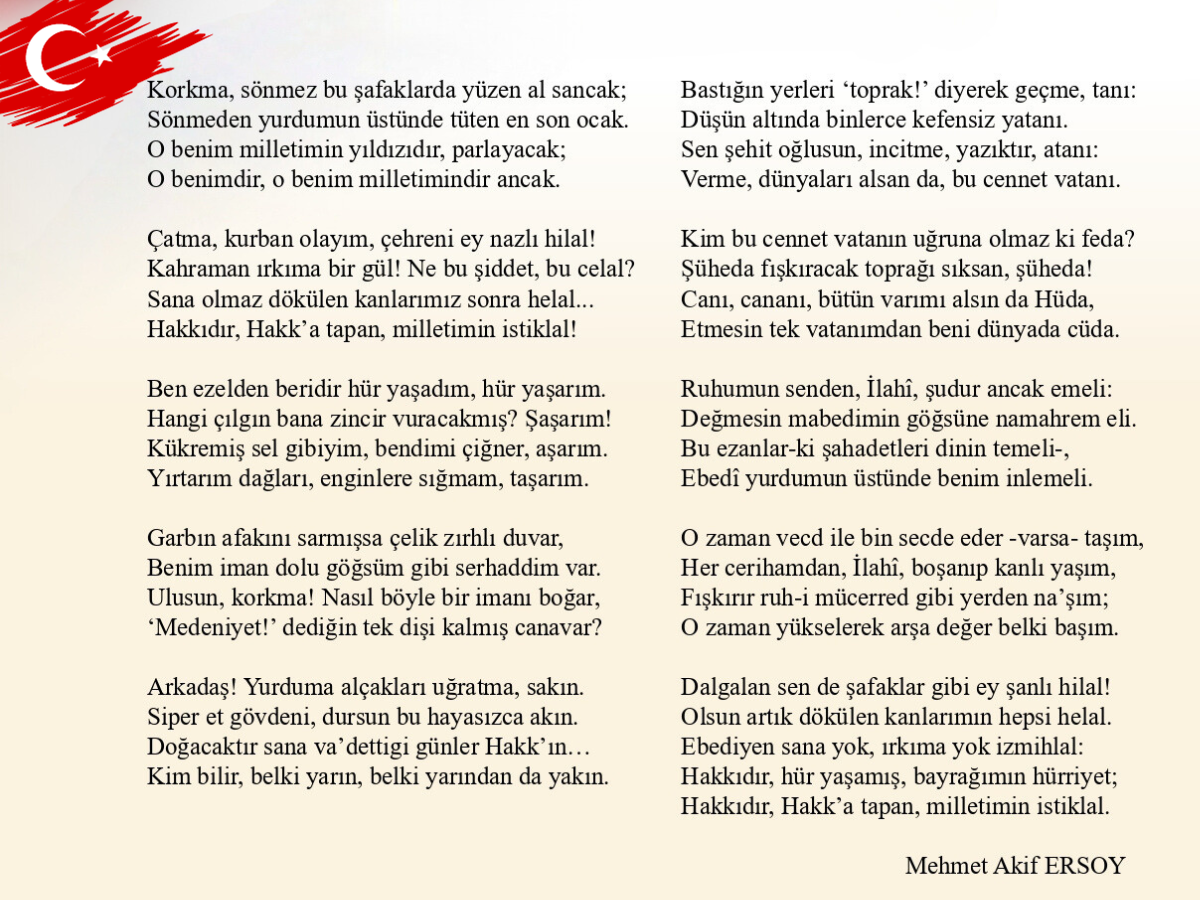

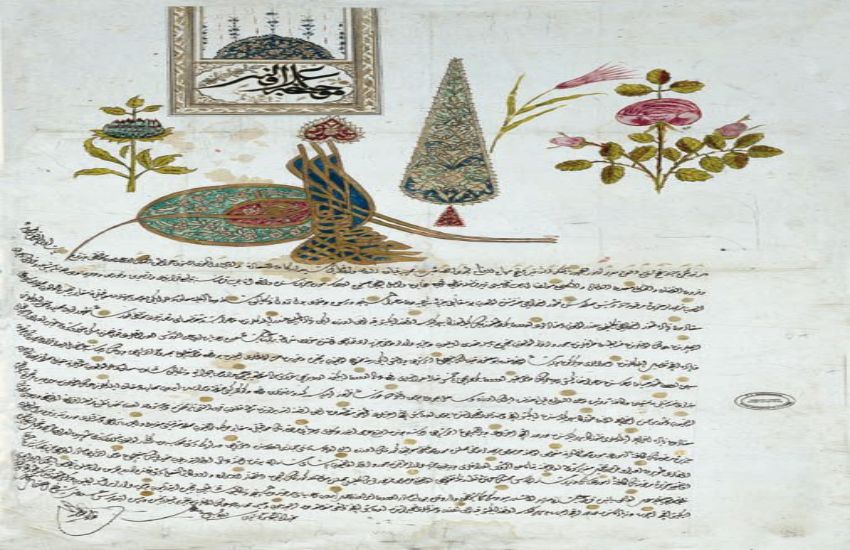

A single brushstroke could seal a man’s fate or grant him an empire’s favor. The Tughra stands as one of history’s most sophisticated calligraphic achievements—a stylized signature that Ottoman sultans used to authenticate their most important decrees. These intricate designs, often rendered in gold or vibrant colors, appeared at the top of imperial letters above the basmala, containing the sultan’s name, titles, and epithets in an elaborate interwoven pattern.

Beyond mere signatures, the Tughra functioned as a royal seal, emblem, and stamp of absolute authority. It graced patents, firmans (royal decrees), and official documents throughout the empire’s 600-year reign.

Origine du mot « Tugra »

The word traces back nearly a thousand years. In his 11th-century masterwork « Dīwān Luġāt at-Turk » (Compendium of Turkic Dialects), Mahmud al-Kashgari recorded the Oghuz Turkic term « tughragh » referring to both the seal (bi) and signature (taw) of Oghuz rulers.

The transformation from « tughragh » to « tughra » happened through a common Ottoman linguistic shift—dropping the guttural Oghuz « gh » ending. Mahmud al-Kashgari also documented the verb « tughraghlanmak, » meaning to receive or apply a tughra to a document. This matches the Arabic « tagh-ghara » (to place a tughra upon something) that Muhammad al-Maqrizi recorded in 1270.

Scholars agree the tughra has definite Turkic origins, though its earliest meaning remains a mystery lost to time.

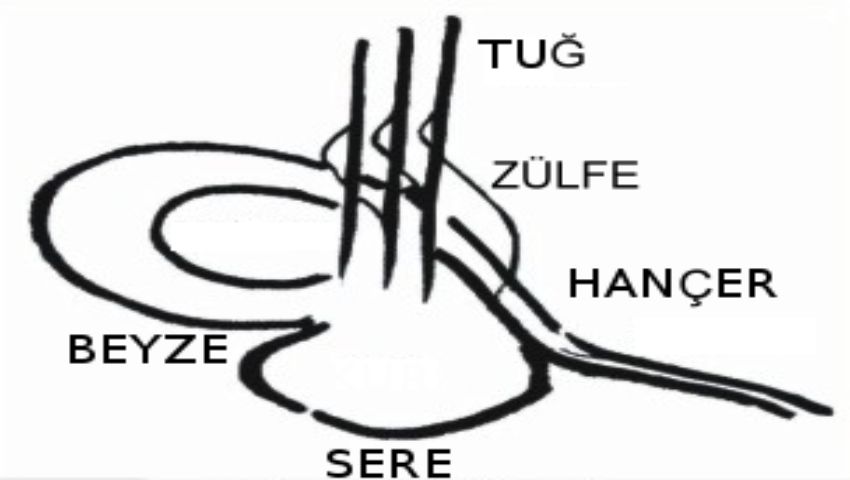

Forme du tughra ottoman

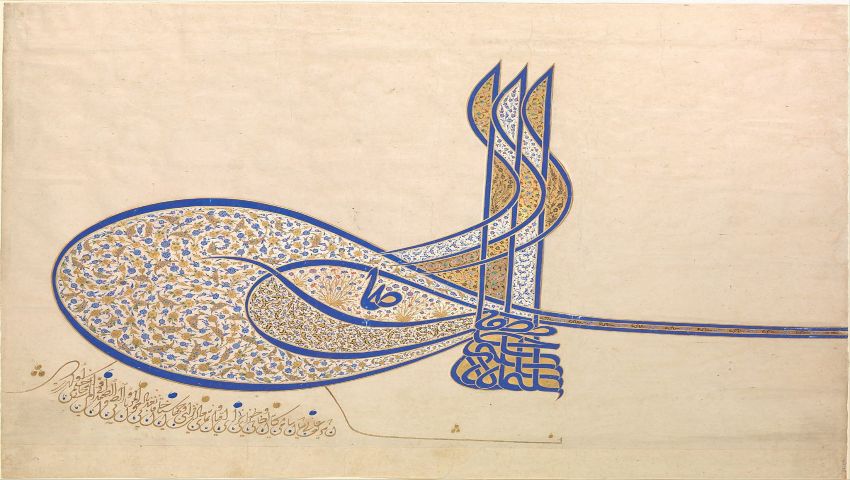

The classic Ottoman tughra design, standardized in the 16th century, weaves together the sultan’s name and his father’s name with titles borrowed from Persian, Mongol, and Arabic traditions—all rendered in Arabic script. The art form grew directly from Ottoman and Arabic calligraphic traditions.

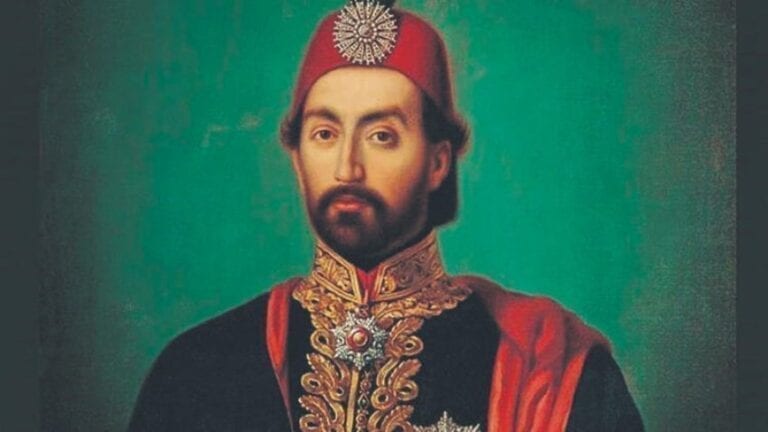

Tracing the evolution from Orhan Ghazi’s simple, preserved tughra to Suleiman the Magnificent’s elaborate creation reveals a steady progression in complexity. Starting with Bayezid II, the designs became increasingly text-heavy and ornate.

The physical dimensions grew dramatically too—from roughly 7 cm wide under Orhan Ghazi to about 40 cm under Suleiman the Magnificent, matching the expanding width of imperial documents.

What unites all tughras is their distinctive layering technique: words stack upon and interweave with each other according to strict calligraphic principles, creating a unified visual composition.

Qui a peint le Tughra

The Nişancı held exclusive responsibility for creating tughras. After this position rose to head the imperial chancellery and gained a seat in the Dīwān (imperial council), Mehmed II’s law required that the Nişancı be a scholar—ideally a professor from a medrese (Islamic school).

The Nişancı typically drew tughras personally in his office or in the Dīwān, or supervised their creation there.

Here’s a clever workaround the Ottomans developed: at the sultan’s command, the Nişancı could add tughras to blank sheets. This allowed decrees requiring urgent action outside the capital to be dispatched immediately.

A representative of the sultan—often a vizier—could then draft a decree on the spot and have it written beneath the pre-made tughra.

The same system applied when the sultan was away from Istanbul and decrees were needed urgently.

Forging a tughra without authorization was punishable by death.

Utilisations du tughra ottoman

The Ottoman Tughra served multiple functions across imperial life:

Authentification des documents

Unlike the Oghuz and Seljuk tughras and seals (damga) that preceded them—known only through scattered references—Ottoman tughras survive in abundance on preserved documents.

At its core, the Ottoman tughra was an elaborate handwritten celebration of the sultan’s official name and titles.

It served as the imperial seal on letters, establishing their legitimacy and certifying their authenticity.

Execution varied widely—from simple ink renderings to precious colored inks to fully painted and illuminated masterpieces. The choice depended on the sultan’s preference, the era’s style, and most importantly, the occasion’s significance and the recipient’s status.

These documents survived remarkably well because they were typically rolled (sometimes folded) and stored in silk pouches or ornate boxes.

Some of the most lavishly illuminated foundation deeds (vakfiye) were preserved as page collections or bound with rigid covers.

Imperial letters bearing tughras covered everything: establishing foundations, appointments, promotions, diplomatic missions, authentications, property transfers, and dispute settlements.

Sur les bâtiments et les pièces de monnaie

Tughras became architectural features and decorative elements, particularly from the 18th century onward. Sultan Mahmud II’s tughra, for instance, was installed as a sculpture alongside Suleiman the Magnificent’s seal in a prime location—above the mihrab of the Yashar Mehmed Pasha Mosque in Pristina, built in 1834.

At Topkapı Palace in Istanbul, tughras appear throughout later construction phases as both decorative jewelry and imperial symbols. A striking example sits to the right of the « Gate of Felicity » (Bab-ı Saadet) entrance, which was renovated in the rococo style during the 18th century.

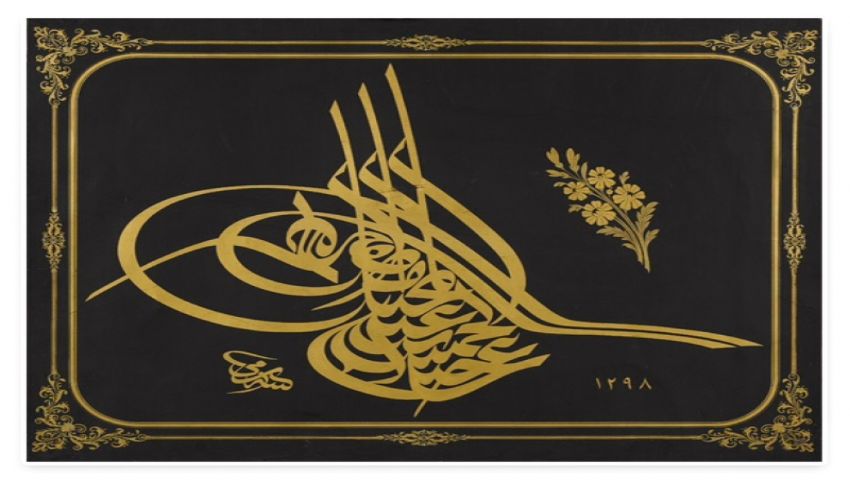

Abdülhamid II’s tughra appears at the German Fountain in Istanbul, constructed in 1900 as a gift from German Emperor Wilhelm II. Look up inside the dome and you’ll spot medallions alternating between Abdülhamid II’s tughra and Wilhelm II’s monogram—rendered as mosaics above the eight column capitals.

The oldest known Ottoman coins bearing tughras date from Murad I and Emir Süleyman—the latter proclaimed sultan in Adrianople before being strangled in 1410 on his brother Musa’s orders during the interregnum (1402-1413).

After this period, sultans regularly minted tughra-bearing coins, starting consistently with Mehmed II and becoming more frequent under Suleyman II.

Around 1700, a type of Ottoman gold ducat became known simply as « Tughrali » (bearing a tughra).

Even today, though modern Turkish coins no longer feature tughras, the obverse (heads side) is still called « tura » in Turkish—a linguistic fossil from the imperial era.

Over the centuries, the reigning sultan’s tughra appeared on countless objects—official, semi-official, and private alike. These included gravestones, medals, flags, postage stamps, weapons, saddle blankets, and household items from the sultan’s personal collection.

The Ottoman Tughra Ban and Modern Restoration

Law No. 1057, enacted in mid-1927, mandated removing tughras along with Ottoman coats of arms and inscriptions from public and state buildings throughout the new Republic of Turkey.

Under this law, tughras from state and municipal structures were to be preserved in museums. If removal would damage their artistic value, they could be covered in place. The Ministry of Culture held authority over implementation decisions. The law specifically targeted tughras displayed as symbols of Ottoman rule.

However, the situation has changed dramatically. While Law No. 1057 technically remains on the books, its strict enforcement ended decades ago. Since the 2010s, Turkish authorities have actively restored and preserved tughras as protected cultural heritage rather than symbols to be hidden. Today, you can see tughras prominently displayed on Istanbul University’s historic gate, throughout major mosques, and across palace complexes like Topkapı. The Turkish Ministry of Culture now treats these calligraphic masterpieces as treasures to be celebrated, not remnants to be erased.

Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent

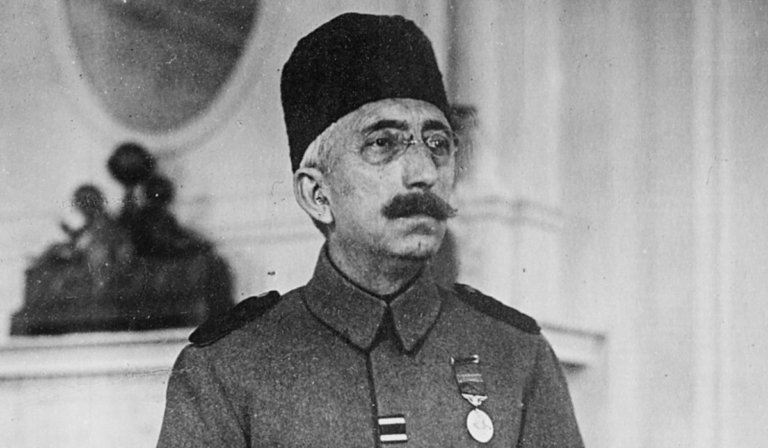

Tughra of Sultan Abdul Hamid II

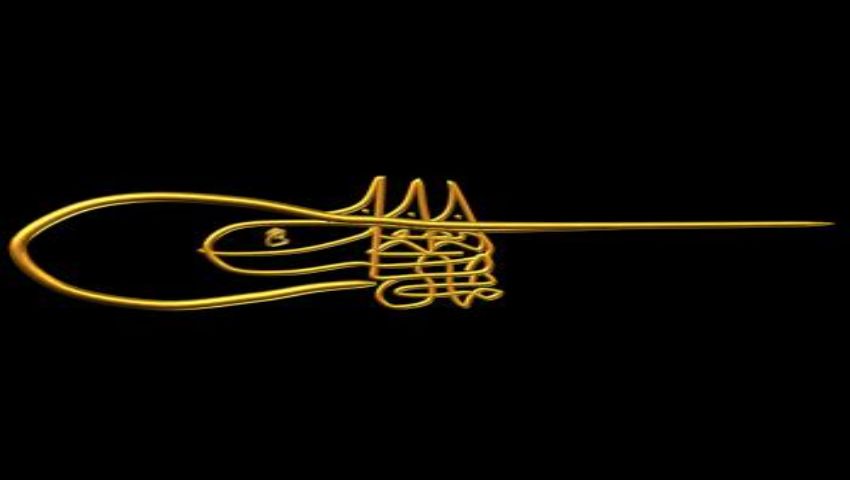

Tughra of Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror