Turkish Carpet Art: The Hidden History Woven Into Every Knot

Table of Contents

Why has the Oriental rug remained a definitive status symbol in the West for over 500 years? It is no accident of fashion. For the nomadic tribes of Central Asia, these carpets were never mere floor coverings. They were a “portable garden” in the barren steppe, a mobile palace floor, and a sanctified prayer space all rolled into one.

These woven works are not just decoration; they are the archival memory of a civilization. The story of Turkish carpet art is a journey that began over two millennia ago, transforming from the practical insulation of Asian yurts to the high altars of European cathedrals. To understand these carpets is to understand the very soul of Anatolia.

The Origin: The Pazyryk Carpet and the “Turkish Knot”

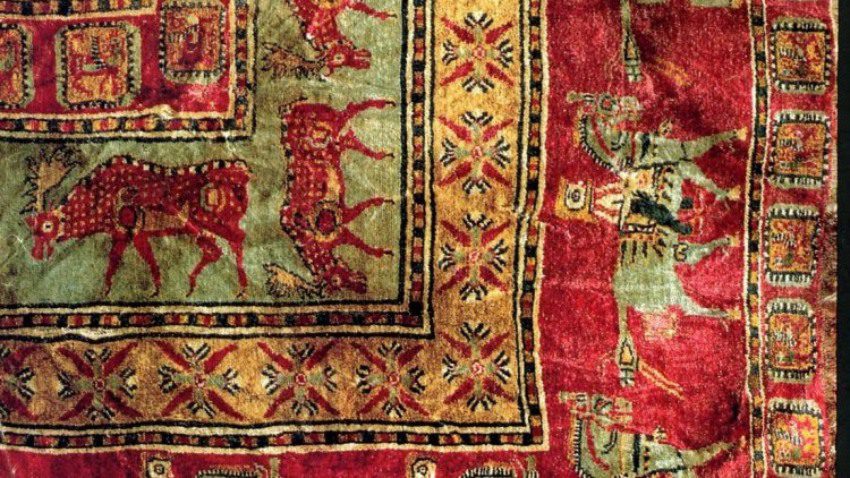

For centuries, the true origin of the knotted carpet was a matter of speculation. That changed in 1949, when an archaeological discovery rewrote the history books. Deep in the ice of the Altai Mountains, researchers excavated the Pazyryk Kurgan (burial mound) and found the world’s oldest surviving carpet. Dating back to the 4th or 3rd century B. C., it had been frozen in timeand condition.

Why this discovery shattered previous theories:

- Impossible Technique: The Pazyryk carpet isn’t a primitive prototype. It is incredibly fine, boasting approximately 3,600 knots per square decimeter (about 230 knots per square inch). This proves that carpet weaving was already a mature, sophisticated art form 2,500 years ago.

- The Gördes DNA: Crucially, the rug was crafted using the symmetrical double knot, known today as the “Turkish Knot” or Gördes knot. This provides the strongest link to the early steppe peoples and serves as the ancestor of the Turkish tradition.

- Visual Storytelling: With its intricate borders of horsemen and elk, it mirrors the life of Eurasian nomads. While scholars still debate the exact ethnicity of the weavers (Scythian or Hunnish Turkish), the cultural lineage is undeniable.

The Seljuks: Geometry as Theology

When Turkish tribes migrated into Anatolia starting in the 11th century, they brought their looms with them. However, under the Seljuk Empire (13th–14th centuries), the style underwent a dramatic evolution. The carpets of this era abandoned fluid lines for strict, powerful geometry.

These patterns were not arbitrary. They were visual representations of the Islamic concept of Tawhid (unity and infinity). The geometric forms often octagons and rhombusesare arranged in a way that suggests they continue infinitely beyond the physical borders of the rug. It was an artistic attempt to capture the infinite nature of the Divine within a finite space. This geometric mastery also parallels the rise of Turkish ceramics and tiles, which dominated the aesthetic of the era.

Where can you see these rarities?

The few surviving examples were found in sacred spaces where they were preserved for centuries:

- Alaeddin Mosque in Konya: Eight of the most significant early carpets were discovered here.

- Eşrefoğlu Mosque in Beyşehir: Three masterpieces were recovered from this historic wooden mosque.

The “Ming” Influence: When Dragons Came to Turkey

By the 14th and 15th centuries, the visual language shifted again. Stylized animal figures began to appear, signaling a cultural exchange along the Silk Road. The most famous example is the so-called “Ming Carpet” (often termed the “Dragon and Phoenix Carpet” by historians).

Discovered in a church in Central Italy, this rug depicts a battle between a dragon and a phoenix. This imagery is distinct evidence of Chinese artistic influence filtering into Anatolia via the Mongol expansions, blending Far Eastern mythology with Turkish craftsmanship.

Ottomans & Europe: The Renaissance Status Symbol

Here is a fact that surprises many art lovers: many classic Turkish carpet patterns are named after European painters, not Turkish cities. Beginning in the 15th century, the Ottoman Empire exported these rugs to Europe in massive quantities. They were so prohibitively expensive that they were rarely walked upon. Instead, in paintings by Hans Holbein the Younger or Lorenzo Lotto, you will see them draped over tables or hanging from balconies as the ultimate flex of wealth.

Art historians categorize these carpetsmostly woven around Uşak and Bergamaby the painters who immortalized them:

- Holbein Carpets (Type I, IV): Defined by small, geometric “Gül” (rose/octagon) motifs and infinite repeating patterns. They represent classical Ottoman elegance.

- Lotto Carpets: Instantly recognizable by a bright yellow arabesque grid on a deep red background.

Palace Carpets: The Summit of Luxury

While the villages of Anatolia kept the geometric tradition alive, the Ottoman court workshops (the Ehl i Hiref) developed a completely different aesthetic for the Sultans. Here, wool was replaced with silk and gold thread.

Influenced by Persian art following the Ottoman conquests of Tabriz and Cairo, the designs became fluid, floral, and naturalistic. The rigid geometry melted away, replaced by the “Four Flowers” style: tulips, carnations, roses, and hyacinths. These weren’t just pretty flowers; the tulip, in particular, became a symbol of the divine and the emblem of the dynasty itself.

A Living Heritage

A Turkish carpet is never just an object. It is a historical document that spans from Central Asian nomad camps to Seljuk mosques and into the throne rooms of Europe. When you walk through a bazaar today, perhaps while shopping in historic cities like Edirne or Istanbul, you aren’t just buying wool and dyeyou are acquiring a piece of infinity.

Buying one of these pieces often involves a ritual of its own. If you find yourself in the Grand Bazaar, mastering the art of haggling is essential to the experience. It is the final step in a centuries old tradition of trade.

Do you want to bring this traditional design into a contemporary space? You don’t always need an antique. Many modern Turkish retail giants and furniture manufacturers continue to reinterpret these ancient motifs, blending 2,000 years of history with modern comfort.